The tranquil streams of Bishop Creek Canyon belie the powerful economic impact they had on Nevada and California in the early 1900s. The canyon’s ideal combination of water and gravity produced hydro-electricity, creating great wealth for two states and two dominant industries. But practical use of electricity was in its infancy. Just a few decades earlier those who consumed it had to live close to power generators. For miners in the western deserts, that was a problem.

At the turn of the century, in the American southwest, isolated mining operations began incorporating the use of small fuel-based generators. But fuel was expensive to buy and transport, so scaling a  mining operation was cost prohibitive. As a result, miners were powerless to cost effectively extract and process the spectacular riches being discovered.

mining operation was cost prohibitive. As a result, miners were powerless to cost effectively extract and process the spectacular riches being discovered.

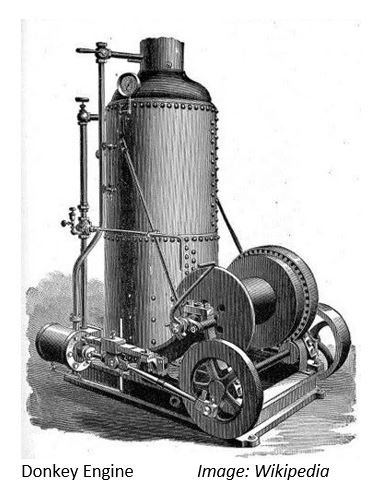

Such was the case for Tonopah and Goldfield, Nevada in the late 1800s. So called “donkey engines” strained to keep up when ore hoists got longer and shafts got deeper. Old steam engine technology relied on water that was locally scarce, boiled with dwindling wood supplies and expensive coal; these boom towns threatened to go bust. But that was about to change after the arrival of two men from Colorado.

Backed by Denver investors in 1904, hydraulic engineer Loren Curtis and former railroad official Charles Hobbs traveled to Goldfield and Tonopah with their “grubstake” money to purchase mining claims. The profitable claims were gone, but they quickly realized that expansion of Tonopah and Goldfield had reached its limit without a cheap source of power. One of the men from Denver looked to the west, to the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

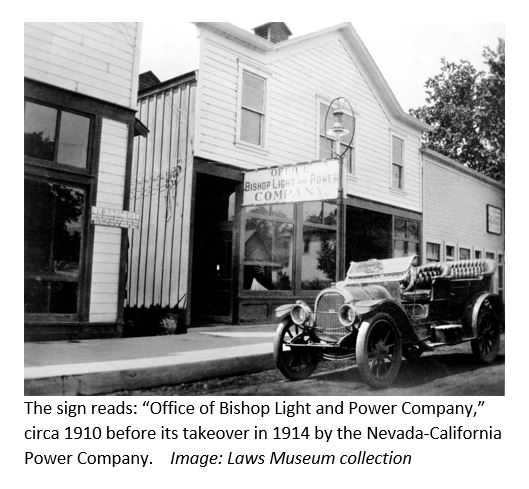

Knowing the potential of hydro-electric power, Curtis used their dwindling “grubstake” money to travel to Bishop Creek Canyon near Bishop, California. When he arrived, a small hydro-generator was already supplying electricity to the Bishop Light and Power Company. But Curtis saw the canyon’s potential to generate a fortune, and wired Hobbs saying he had the “world by the tail.” Hobbs, however, did not share his excitement.

Hobbs felt Curtis was wasting money, and said they should head back to Denver. But after numerous back and forth messages, Hobbs relented and traveled to Bishop Creek. When he arrived, he too was convinced.

Returning to Denver they assembled a group of investors, including Colorado U.S. Senator Lawrence Phipps. The group quickly assembled $300,000, and on December 31, 1904 the Nevada Power, Mining and Milling Co. was formed. Their urgent action was for good reason.

A rival group planned to harness hydro-electric power from the Owens River Gorge, and another group would harness the Owens River itself. The San Bernardino Sun Telegram reported: “The [Nevada] mine owners...were paying $12 a ton for Utah coal and up to $7 per 1,000 gallons of water to use in steam boilers. They would not wait for the arrival of a second power line.” The Sun Telegram revealed that “the first company to reach Goldfield would get the business.”

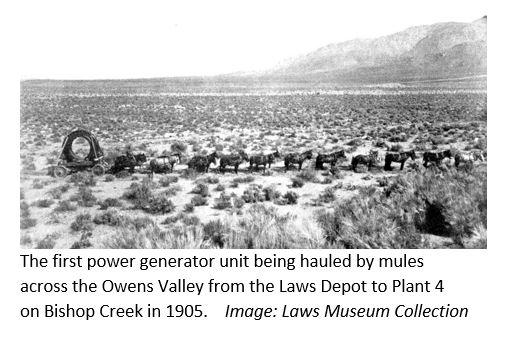

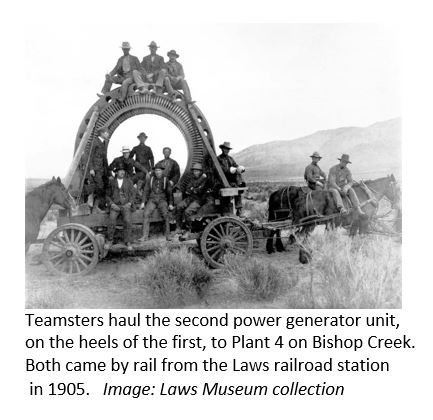

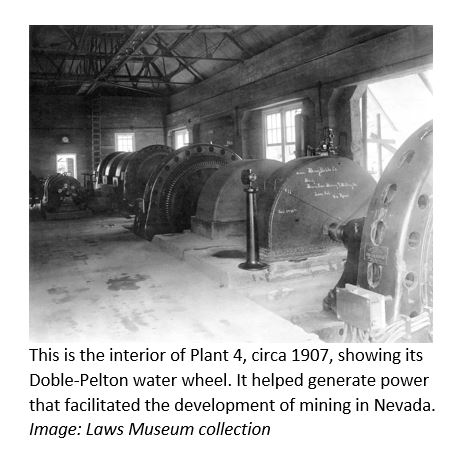

On January 1, 1905, the day after the company formed, construction began on the first generating plant on Bishop Creek near the present location of Plant Four. It would feed one of the world’s longest powerlines at the time, a 113-mile 55,000 volt transmission line from Bishop Creek to Goldfield, Nevada. After they installed a 750-kilowatt generator, they realized it wouldn’t keep up with demand, so another generator was planned. Meanwhile they began their biggest challenge, the powerline.

On January 1, 1905, the day after the company formed, construction began on the first generating plant on Bishop Creek near the present location of Plant Four. It would feed one of the world’s longest powerlines at the time, a 113-mile 55,000 volt transmission line from Bishop Creek to Goldfield, Nevada. After they installed a 750-kilowatt generator, they realized it wouldn’t keep up with demand, so another generator was planned. Meanwhile they began their biggest challenge, the powerline.

In the dead of winter, and with no formal power agreement with Nevada miners, a survey crew began laying out a path up and over the White Mountains to the east. And right on their heels was the pole-line construction crew, carrying their portable sawmill with them, ready to build the poles with native timber...Bristlecone pine.

Mountains to the east. And right on their heels was the pole-line construction crew, carrying their portable sawmill with them, ready to build the poles with native timber...Bristlecone pine.

The tree’s rock-hard wood was ideal for power poles and cross arms. Its stubby bottom and stance were perfect for surviving six months of brutal winter winds and snows in the White Mountains. Scientists at the time were unaware of the significance of the nearly 4,000 year-old trees.

After making it through winter, they endured the brutal heat of summer on the desert floor on their way to Goldfield. The Company, now called the Nevada-California Power Company, left its rivals in the dust, and in just nine months, electricity began flowing to the Goldfield substation.

One of the world longest transmission lines now ran from Bishop Creek Canyon through Bishop and Laws, up and over the White Mountains and sown to Oasis in Fish Lake Valley. The line traveled 12-miles east to Palmetto, north to Silver Peak Nevada, and then to Alkali just west of today’s Highway 95. The transmission line split at Alkali: one line headed south to Goldfield and the other north to Tonopah, Nevada. It was just the beginning.

Power hungry mines clamored for electricity. In 1907, the line peeled off at Palmetto, traveling 60 miles southeast to Rhyolite, Beatty, and a dozen other mines and camps. Miners began feasting on power.

Power hungry mines clamored for electricity. In 1907, the line peeled off at Palmetto, traveling 60 miles southeast to Rhyolite, Beatty, and a dozen other mines and camps. Miners began feasting on power.

Power and telephone lines were strung at an unprecedented rate, this time from Millers Camp near Tonopah to Manhattan, 40 miles to the north. The June 1909 edition of The Los Angeles Herald reported, “The Nevada-California Power Company has broken the world’s record in line construction.” Five wires, a mile each, were hung together each hour; six men installed a total of thirty miles of wire each six- hour shift.

Cheap Bishop Creek electricity gave rise to a period of great prosperity for Nevada. The demand for power grew, as did the power system. By 1908, five generators were cranking out power at Plant 4.  Nevada Power then purchased stock in the Hillside Water Company allowing them to building of Plant 2 upstream and Plant 5 downstream, ultimately adding Plants 3 and 6. Plant 1 was never built.

Nevada Power then purchased stock in the Hillside Water Company allowing them to building of Plant 2 upstream and Plant 5 downstream, ultimately adding Plants 3 and 6. Plant 1 was never built.

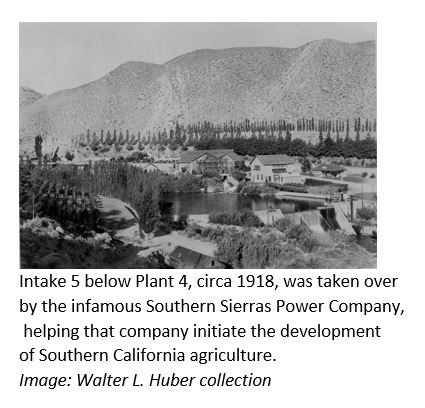

Constant water flow was maintained at the Hillside Reservoir, known today as South Lake. After enlarging the reservoir and fine tuning the generating system, it became so powerful it exceeded the needs of the Nevada mines and the local area. So the company looked to sell power to Southern California.

In 1911, a subsidiary of Nevada-California Power was created to capitalize on the growing agricultural markets in Southern California. The now infamous Southern Sierras Power Company was born, and took over control of Plants 5 and 6. Their first goal: build the longest transmission line the world had ever seen.

The finished 238-mile ”Tower Line” stretched from Bishop Creek, down the Owens Valley, across the Mojave Desert, over Cajon Pass, and down into San Bernardino, eventually creating a highway. According to the book Iron Men and Copper Wire, “the supply and patrol road built alongside [the power line]  was later reconstructed...as U.S. Highway 395.”

was later reconstructed...as U.S. Highway 395.”

Southern Sierras Power began feasting on smaller electrical generating companies, further amassing the company’s influence and power. Electrified ice plants refrigerated fruits and vegetables enabling Imperial and Coachella Valley to grow from a mere 50 people, to over 65,000 in 20 years.

But powering this growing empire required control of three Bishop Creek reservoirs which provided water for hydro-electric power generation and local farmers. Release of water was dictated by the needs of Sierra Power, not the needs of farmers and residents. Resistance to the company came to a head in 1920. The Owens Valley Herald began running stories reflecting the growing anger over water control, labor disputes, and business practices of the Southern Sierras Power Company.

In the May 12, 1920, a Herald headline blared, “TIME TO DO SOMETHING.” The paper said it is “time for the people of this valley to take a decided stand upon the actions of the Southern Sierras Power Company in trying to get an absolute monopoly in the electrical business of Owens Valley has arrived.”

Even the Valley’s nemesis was defended: “[if a]stand is not taken at once...to thwart them in their present endeavors before congress to eliminate the City of Los Angeles as a competitor...the people will someday...wake up to the fact they are hog tied by this corporation.”

At the same time, Inyo County filed suit against Southern Sierra Power’s reinterpretation of the franchise fee. Inyo received a check for $142.89 instead of $2,092.13 they were owed.

Then hearings began over water rights on Bishop Creek. A.E. Chandler, the former State Water Commissioner, who The Owens Valley Herald said was “one of the best known authorities on water in the West,” presided in court. The result was the “Chandler Decree” which is still enforced today.

By the 1930s, the Southern Sierras Power Company’s empire began to decline. The Depression took its toll and cheap energy from the Colorado River reduced the need for Bishop Creek power. In 1941, California Electric Power Company, later known as Calectric, took over. And in 1964 the Bishop Creek power system was purchased by Southern California Edison.

Bishop Creek hydro-electricity brought great prosperity to Nevada, ignited massive growth of agriculture in Southern California, and created a powerful company. For a brief period in history they all flourished and fattened up, as they all feasted on power.

(Images courtesy of Laws Railroad Museum & Historical Site and Walter L. Huber collection)

Copyright © 2018 Ted Williams. All Rights Reserved